During this generation a world came to an end – and another one was born. The best-remembered midwife of the new appearance was an instrument maker and Mathematics professor at Padua University in northern Italy, part of the Most Serene Republic of Venice. In 1609 Galileo Galilei heard that a man from Holland was offering a new optical instrument for sale in Venice. By looking through this device containing a concave and a convex lens, distant objects were magnified and easily visible. Galileo advised his patron to refuse the purchase, and set about making one himself. He duly made one with greater magnification, and offered it as a gift to the government of Venice. In return they renewed his university professorship, which was about to expire, and made the position permanent. For a seafaring nation like Venice, such an instrument (which became known as the telescope) was invaluable.

Galileo was probably not the first person to turn the telescope towards the sky, but he was the best placed to publicise his findings. He saw that the night sky contained far more stars than anyone had dreamed of, that the planets were spheres and the stars were points of light. He saw that the planet Jupiter had four satellites. And most significantly, he saw that the planet Venus had phases as our moon does. The logical explanation for the crescent and full Venus at different times was that it circled around the Sun, not planet Earth as previously believed.

Why did this mean the end of the world? The clues are still embedded in our language. Where is heaven? Above us. Where is hell? Below. When a sudden downpour happens, we say the heavens opened. Church art showed vivid depictions of the heavens above us on their high ceilings.

The Triumph of Divine Providence, ceiling fresco in Palazzo Barberini in Rome, celebrates the election of Pope Urban VIII in 1623. This pope presided over the trial which forced Galileo to recant his views.

The Ptolemaic system was the accepted view – literally. God is on high. Hell is beneath our feet. The Earth is the still centre of God’s creation. The planets and stars revolve around it. A Polish canon had proposed in the previous century that it made more sense to think of the Sun as the centre around which the Earth and the other planets revolved. But this was just a theory, and so could be safely ignored. With his telescope, Galileo demonstrated that the Earth-centred system did not fit the observed facts.

This was revolutionary. A person might feel that their entire world view, their sense of reality, was being shaken. It was known that the Earth was round – the globe had been circumnavigated – but that did not invalidate the Earth-centric view. Intuitively, it was absurd to suggest that the Earth was in motion. It felt still! And most significant of all, it called into question the teachings of the church and its interpretation of the bible. No wonder the sense that the world was coming to an end was so pervasive during this generation. However, Galileo and his contemporaries probably felt that a new and more interesting one was appearing.

The world was in motion in other ways too. The rise of Protestantism in central and northern Europe forced the Roman church to revisit its values. What emerged was a celebration of the glory its leaders felt in their religion. The churches and palaces of Rome were lavishly decorated in the new style. The producers of such work started to innovate. Artists from the rest of Europe came to Rome to see what they did.

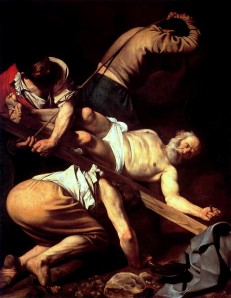

They came to see the works of Caravaggio in particular. He painted with a realism and use of light and dark that was quite new. This painting of the martyrdom of St Peter shows the saint as a struggling old man, not a semi-divine being. And who would have thought of painting a picture that shows an ordinary trouser-clad bottom so prominently!

One of the visitors was Peter Paul Rubens, from Flanders (now Belgium).

This lovely, tender, direct painting of his five-year old daughter Clara also shows a realism that had not been attempted before.