Many people alive in this time felt that something was coming to an end. A monk called Gregory, who went on to become pope in 590, wrote that the world ‘was growing old and hoary, hastening to its approaching death’.

He had good reason to say so. These were troubled times.

The latest set of troubles began in the year 536. From Ireland across to China, cold weather and crop failures were reported. It was a year without a summer. The historian Procopius, based in Constantinople, wrote: “during this year a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness… and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear”.

Evidence from ice cores says that it was caused by a volcano – and more to were to follow in the next five years.

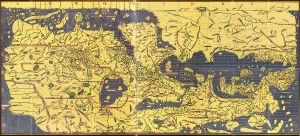

Another source of trouble was the continuing migrations. The changing climate wasn’t a cause of the migrations, but may have exacerbated them. The edges of the Roman Empire – the rivers Danube and Rhine in central Europe, for example, had long been a fragile membrane, with the Empire in the settled agricultural lands surrounding the Mediterranean, and the more mobile alliances of peoples living on the less cultivatable land beyond. The peoples living just beyond the border were traditionally paid to stay put, but that system had already broken down. A couple of centuries previously the groups living beyond the frontier had found out how to work around the Roman policy of divide and rule. They formed alliances, too large for the Roman army to easily defeat, and then either invaded or negotiated a settlement of land within the Empire itself.

And the migrants kept on coming. Around 540 it was the Avars, originating from the Eurasian steppe. They moved into the Hungarian plain in particular, and in so doing displaced the Lombards who were the current occupants. The Lombards then moved south and invaded northern Italy. This region was already suffering from Justinian’s brutal recovery of it from the previous wave of invasions (by the ostrogoths), and so had nothing left to resist the next set of incomers. The Lombards moved in and used it as a base for further expansion. Part of northern Italy is still known as Lombardy.

And it got worse. Like the Mongols seven hundred years later, the Avars brought the bubonic plague. It reached Europe and the Mediterranean in 541, and was devastating. The creaking bureaucracies of the Roman Empire based in Constantinople and the Sasanian Empire based in Ctesiphon had to cope with a reduction in tax revenues resulting from the loss of up to a third of the populations. The revenues that were used to pay the armies were reduced, and consequently so were troop numbers.

The economic basis of the Roman and Persian empires was agricultural surplus. The estates produced more food than the inhabitants could eat, and paid taxes to the central administration in Constantinople or Ctesiphon. The richest agricultural region was in the middle east, between the two empires. So it made sense to concentrate what was left of the armies there. This was a period of continual war between Constantinople and Ctesiphon, to gain control of the near east from Anatolia to Mesopotamia. Sometimes the Persians took control, at others the Romans. The conflict must have been a drain on resources and difficult to sustain with everything else that was going on.

One of the other things that was going on was endless argument among christians. Christianity had been the official religion of the Roman Empire since 313, but that was a mixed blessing to most christians, as there were many versions of their faith. Empires, it would seem, are not good with ambiguity. So the continual arguments about the nature of Jesus (for example, was he a human like the rest of us, or divine and co-eternal with God, or both?) were not welcome. Anyone who strayed from the official view of the Roman church (that Jesus incarnated in a physical body but was also divine) was deemed a heretic.

Pope Gregory adhered to a strand of christianity that had more successfully integrated into the Roman church. The happiest period of his life, he said, was when he could shut all the troubles out and get on with being a monk. He followed in the footsteps of Benedict of Nursia, who died around 545. Benedict had pursued the ascetic strand of christianity and formalised it into a rule, which he applied in his new monastery at Monte Cassino in the south of Italy. His rule book had 73 chapters, covering the varieties of monasticism, the authority of the abbot, how to manage the day-to-day life of the monastery, even down to what the monks should wear in bed. Each monastery was a self-contained unit, answerable to its abbot.

Gregory turned his own family estate into a monastery – which for me is a clue as to what was going on. This was a continuation of the Roman economic model, of an estate providing an agricultural surplus. The estate was no longer the property of one aristocratic family, but was a monastery ruled by an abbot (or abbess). When times grew hard in the territories around Rome as the Lombards ventured further south, Gregory could call on the surplus from the monasteries to feed the displaced people. His success in doing so led to the foundation of the Papal States, a swathe across central Italy ruled directly by the papacy for the next 1400 years.

Gregory is also the source of one of the best-remembered bad puns from late antiquity. The story goes that he saw some blond slaves in the slave market in Rome. On enquiring where they were from, he was told they were Angles. ‘Not Angles but angels’, he is said to have replied. Gregory sent one of his monks, by the name of Augustine, to the land of the Angles to convert the pagans. Augustine set up his first monastery in Canterbury. Perhaps that set the stamp for christianity in England – the monastic system. And maybe that is why, a millennium later, Henry VIII targeted the monasteries. They followed the Roman model, owned large tracts of rich agricultural land across the country and did not answer to the king.

Emperor Justinian also had the basilica of Hagia Sofia built in this period, after its predecessor was burned down in riots. Later it was converted to a mosque, but the original structure is still there.