Looking backwards from the generation of the reformation, this period is colourful, exuberant, lively: a fascinating time to be alive.

This was the High Renaissance, where artists gave themselves the permission to play with the palette and push back the boundaries of what was possible. Michelangelo painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with images of the Creation as described in the bible.

Arguably the most famous painting in the world was completed in this period: The Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci.

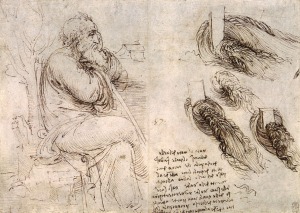

Leonardo had insatiable curiosity. His anatomical drawings predate those of Vesalius (who we met in generation 478) by a couple of generations, but were purely for his own interest. The educated elite would have ignored them anyway – he didn’t write in latin. He developed flying machines, he drew plants and animals, he tried to understand the way water flows … no wonder he hardly ever finished anything.

There were other artists, both in Rome and elsewhere. Further north in Italy, Titian painted exuberant colourful paintings.

Here is his allegory of sacred and profane love.

And further north still, Albrecht Durer in Germany painted with a realism that is not out of place today.

I think this explosion of creativity points to something else, that we can see in this self portrait. We can see an individuality, with the expression that belongs to what was going on in that person at that moment. As we go further back in our story, we lose that ‘warts and all’ sense that comes out of these paintings. Earlier portraits look wooden and expressionless.

This is Durer’s portrait of the banker Jakob Fugger, the man who bankrolled the sale of indulgences in northern Europe that provoked the Reformation in the next generation.

Another new world was coming into view – the one across the Atlantic. The most famous traveller of the time was not Columbus (who had first crossed the Atlantic in the previous generation) but Amerigo Vespucci. He was a multi-talented Florentine (as were Leonardo and Michelangelo) and was the first to report back that the continent they had reached was not Asia, as Columbus had thought, but a new one not described by Ptolemy. It made sense at the time to name the continent after him, and so a German mapmaker called it America. The name stuck and was taken up by Mercator a generation or so later.

From America there arrived new foods – potatoes, maize, cocoa. Tobacco arrived too and also a horrific disease. Syphilis, which was endemic in the Americas, appeared in Europe at this time.

Florence must have been an exciting place to be. Another talented Florentine was Niccolo Machiavelli. He wrote ‘The Prince’ during this period. It is a pragmatic, dispassionate manual for the political classes, assessing policies and strategies not on their moral basis but their effectiveness. He admired the strategies of the Borgia pope Alexander VI, who ruled during this period, for using the papacy as a means to extend his family’s power. Subsequent generations did not take such a neutral view of the Borgia family, especially of Alexander’s murderous son Cesare. We can perhaps trace our suspicion of the devious and manipulative motives of politicians back to the influence of this book.

But my hero from this generation is a man from the Netherlands who, in the spirit of the times, invented his own job description. Erasmus of Rotterdam was clever, witty, well-informed and interesting. He travelled around Europe as a man of letters, staying wherever he could explore his ideas and entertain his hosts. He was the original networker: he had hundreds of correspondents, some of whom he never met. He and his friends took the ideas of the classical Greek and Roman authors – and brought them up to date. The movement came to be known as humanism.

He retranslated the bible into latin. The translation by St Jerome from over a thousand years earlier, the Vulgate Bible, was still the official version. Erasmus made some changes. For example, in the Vulgate Bible Moses was described as having horns, because of Jerome’s translation from the Hebrew of a word which more probably meant ‘radiant’. Erasmus decided that the more likely meaning was that Moses came down from the mountain with a shining face rather than horns on his head.

Here is Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses from the same period, with horns.

Inspired by the stories of the new world, Erasmus’ friend Thomas More wrote ‘Utopia’, about an imaginary society founded on humanist values of decency, education, mutual respect and responsibility. He put his own ideas into practice: his three daughters received the same level of education as his son. Another of their friends, John Colet, set up St Paul’s School, with entry requirements based on merit rather than finances. One of Erasmus’ most famous books was entitled ‘The Praise of Folly’. The title was a pun on the name of Thomas More (‘folly’ is ‘moria’ in Greek) and was written while he was staying at his house. It describes the dangers of taking oneself too seriously, how silliness can ease a difficult situation. It is lighthearted and wise.

I can’t help feeling that something was lost as this generation came to a close. The humanity and enquiry shown by all of these people was not equalled for another three hundred years. The fire-and-brimstone preachers who terrified their congregations with images of hell all date back to the following generation, not this one. Those serious Reformation preachers of the 1520’s and onwards believed that humanity was born in sin and that nothing any of us did could change that. Not an outlook likely to lead to a sunny disposition. One can’t imagine Martin Luther or any of his fellow preachers writing a book in praise of folly.